Nana Asma’u bint Foduye, the legendary Islamic scholar and poet of the 19th century was born alongside her twin brother Hassan; in Degel in the Hausa state of Gobir. She was given birth to by the Shehu’s first wife who was also his first cousin; Maimunatu, in the year 1793 A.D. She and her brother were the twenty-second and twenty-third children of the Shehu. Her father named her Asma’u meaning “noteworthy” or “beautiful” instead of Husaina as expected by custom. She was named after the extraordinary seventh century woman Asmā’ bint Abī Bakr, a sister to Nana Aisha (R.A), the wife of the Prophet (S.A.W).

According to Waziri Junaidu (1957), her brother Hassan died just seven months after the death of Shehu at the age of 25. While according to Murray Last (1967), he died at the age of 23. Asma’u lived for 72 years and the approximated year of her death falls between 1864-1865. She was born in the time of conflict between her father and the Gobir rulers.

The first ten years of Asma’u’s life were devoted to scholarly study. Her life was relatively stable until the emigration of her community from Degel to Gudu which marked the start of the Jihad when she was just 11 years old. Asma’u struggled to continue her studies through a decade of itinerancy and warfare. She grew up in a household of learned, devout individuals whose profession was scholarship. She studied Islamic philosophical texts on prayer, mysticism, legal matters, fiqh (which regulates religious matters), tawheed (dogma) and others. She also studied arithmetics and Arabic literature. She was taught by her father and her step mothers Hauwa’u (Inna Garka) and Aishatu (Gabdo), the two women that brought her up after the death of her mother two years after she was born. She also studied under her brother Muhammadu Bello, her sister Khadija —who were all great scholars of that time— and later on under her husband and other scholars.

She got married to Uthman bin Abī Bakr also known as Gidado dan Laima, a close friend and chief aide of her brother Muhammadu Bello at the age of 14-15 in the year 1807-1808. Her marriage coincided with the time the attack on Gobir was launched. She was taken to Gidado’s house at Salah (where her brother lived when her father was in Gwandu). She was about 18 years younger than her husband and was not his first wife.

According to Boyd and Mack (1997), Asmau gave birth to her first child Abd al-Qādir in the year 1810. And in another book contradicting themselves Boyd and Mack (2000) mentioned that she gave birth to the first of her six children at the age of 20 in the year 1813 who died as an infant. It is important to note that Abd al-Qādir was her first surviving son and not the first son. Murray Last (1967) stated that Asma’u gave birth to five sons and even acknowledged the death of one of them. However, a list by M.S. Maniya in his book “Tarihin Sahabban Shehu” shows that Asma’u had six children in the order;

- Muhammadu Sa’ad (died as an infant)

- Abd al-Qādir

- Ahmad

- Uthmanu

- Abd al-Allah Bayero

- Muhammadu Laima

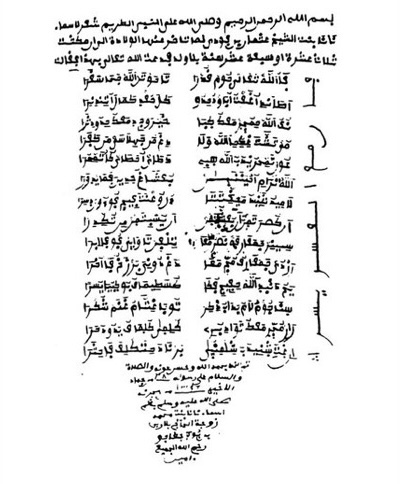

Nana Asma’u, worthy of every scholarship attention in the world authored about ninety authentic works in several languages. She was among the scholars of the highest order in the 19th century. She wrote in the Islamic literacy tradition using Arabic script (ajami) to compose poetic and narrative treatises in Hausa and Fulfulde in addition to Arabic. Her works were written with vegetable dye inks on unbound sheets of paper and kept together in a leather book bag known as gafakka in Hausa.

Nana Asmau’s works included works on theology, history, politics, instructional works for new converts to Islam, reminders, warnings, meditative works, praise songs and so on. She also wrote three books in Arabic one of which was on Islamic medicine titled “Tabshir al-Ikhwan bit Tawassuli bi Suwar al- Qur’an Indal Khaliqil Mannan” which talked about diseases and the Qur’anic verses that cure them.

Her very first work “The Way of the Pious” was written in the year 1820, three years after the death of Shehu. She also cooperated with her brother Caliph Muhammadu Bello in literary ventures which included translating, adapting and versifying a work on sufi women. And after the death of Bello in 1837, she and Gidado composed nine works which have been the biographical basis of all subsequent works on the jihad.

Asma’u served the caliphate for up to fifty years from the year 1815 when her father visited her in her matrimonial home to indicate his approval. She taught both men and women, was fluent in four languages including Tamajek, the language of the Tauregs. Asma’u’s multi-lingual scholarship served to convey the political focus of her messages to audiences who spoke different first languages, either Arabic, Fulfulde or Hausa. The works in Fulfulde circulated among the ruling elites and constituted her messages to them, while works in Arabic might have been sent across the Maghrib to other Arabic scholars. Asmau had received letters from scholars as far away as Mauritania which indicates that she communicated with others throughout the West African intellectual community.

Asma’u, being brought up in a family of the Sufi Qadiriyya was focused on righteousness and pursuit of knowledge. Material things were not of paramount importance and were even considered a distraction. She was well versed in sufi philosophy, she had memorized the Qur’an at a young age and was familiar with books on the topics written by her father the Shehu, her brother Muhammadu Bello and others. Her command of sufism is clear in her poem “The Path of Righteousness” written when she was only 27 years old. In the poem, she specified nine character traits that a devout sufi should cultivate following the pattern set by the Shehu in his “Kitāb ‘ulūm al-mu āmalah.”

Asma’u had an enquiring mind at a very young age and this assertion is supported by a story related by her husband Gidado, in his book “Rawd al-jinan.” Gidado related that there was a time when she spoke to her father with the language of the Tauregs at the age of twelve. And when he enquired of her where she had learned to speak the language, she told him that a Taureg concubine of her brother had taught her. So the Shehu tested her by asking her the Tamajek words for earth, sun, moon and so on. Until he came to salt and she didn’t know the word. So he said to her, “You have been going to the Taureg camp, asking them words, and writing them down.” Then she admitted her guilt and promised not to lie again. This story shows us that she was accustomed to leaving the house to learn all that she could due to her thirst for knowledge and it also shows us the value of truth in her family.

Asma’u was as comfortable in intellectual debates as she was in domestic endeavors, understanding both to be of equal significance to life in this world. Her responsibilities went beyond teaching. She was an efficient manager and a consummate meditator. At the age of twenty seven, she and her husband facilitated the organization of the Shehu’s works after his death. Her husband often being away to attend his duties left most of the work to her. A task which required her quadri-lingual skills, an intimate knowledge of the Shehu’s entire corpus of writings, and her extraordinary memory; which allowed her to catalogue innumerable pages of unbound texts that had suffered decades of use and transportation from one encampment to another during the jihad years. At the same time, Asma’u was responsible for catering to the needs of a household of several hundred people; providing food, clothing and shelter. During this time, her husband was the vizier and thus often departing for an outlying area on assignment, such journeys would have required special preparations and provisions for which Asma’u was responsible.

She must have also been responsible for playing host to the many travelers who arrived at her home to visit her husband, providing them with all the comforts that were expected. She was also instrumental to the success of the jihad campaigns by preparing material goods necessary for both the battle and the itinerant life that resulted from warfare. She made preserved food for the army and crafted containers for food and water, she processed grains and milk products for both immediate and long-range usage. She was also among the women who shouldered the responsibilities for nursing the men wounded in the jihad battles and helped in transporting them as they fled in the face of enemy attack. Asma’u was also known for providing care and training non-Muslim refugees.

By the age of forty, Asma’u’s role as acknowledged leader of women in the community was already established and she was referred to as Uwar Gari (Mother of all). Asmau introduced a Women’s Education System known as ‘Yan Taru where women from different parts of the caliphate visited her in Wurno and Sokoto to learn the five pillars of Islam and how they are to be carried out, instructions from the chapters of the Qur’an, biography of the Prophet (S.A.W), the Islamic ways of life, books on jurisprudence, dogma, hadith, accounts of sufi women in history, and others. She also warned them against lying, fornication, stealing, and diseases of the heart like jealousy.

The ‘Yan Taru was equivalent to distance learning where women around the age of 50 that are past childbearing age and young girls that are about to get married visit to memorize verses and learn how to write and read so as to be able to share their knowledge with the isolated rural women in their localities, when they travelled back home.

In this way, a lot of women were able to learn without leaving their houses and were trained to pass on their knowledge to their kids so as to breed a society of educated men and women. The system of ‘Yan taru was well organized as there were leaders who monitored and organized the women. Their leader; jaji, was responsible for organizing and leading them from their villages to Asma’u. She was in charge of the activities of her people and was distinguished by a hat which denoted her authority. Other posts held were Waziri, Majidadi, Imamu, Bero, Zakara, Zamzana, Attuwo, Mai Taru and Shantali. These people also provided support and care for women of all ages in the system regardless of what their status was.

Asma’u’s younger sister Maryam, a daughter to Shehu’s concubine Mariyatu who married The Emir of Kano —Ibrahim Dabo— returned to her father’s house after the death of the Emir. She became the leader of the ladies living in the hubbare, teaching and working as Asma’u’s companion and aide due to her immense knowledge and commanding presence. After the death of Asma’u, Maryam took over the leadership of the Women’s Educational Movement and likewise after the death of Maryam;her daughter Tamodi (also known as Maryam) who was her deputy succeeded her as the leader of the Movement.

Even after the death of Tamodi, the ‘Yan Taru still visited the hubbare to acquire knowledge from the descendants of Maryam who inherited the room known as “Dakin Mariyatu” where most of the activities of the movement are being held in the hubbare. Because even after the death of Asma’u’s husband, she did not return to the hubbare but stayed in her matrimonial home to continue carrying out her duties. The ‘Yan Taru of this century are more focused on pilgrimage, recitation of poetic verses, nursing of the sick, bathing and dressing the deceased and other services related to society and Islam.

“Talented as she was, Asma’u was neither alone in her intellect nor unique among women in her activism. Indeed, her accomplishments exemplify a long-standing pattern in West Africa of Muslim women’s scholarship and contributions to community.” Jean Boyd and Beverly Mack (1997)

Whatever Asma’u achieved in spreading knowledge, she did so with the help of other women she regarded as co-workers. Taking a look at some verses from her poem ‘Sufi Women’. We’ll see that women in the community of the Shehu were well educated. As even the Shehu himself studied under his mother.

“68 The teacher of women, Habībah

She was most revered and had great presence

69 I speak of Ā’ishah, a saint

On account of her asceticism and determination

70 And Joda Kowuuri, a Qur’anic scholar

Who used her scholarship everywhere

71 I speak also of Biada who was deligent

For her attribute was in reclusion

72 And ‘Yar Hindu, daughter of the Imām

Who was deligent at solving disputes

73 There were others who were upright

In the community of the Shehu; I have not listed them

74 Very many of them had learned the Qur’an by heart

And were exceedingly pious and zealous

75 They never tired of preaching the righteous Faith”

In 1975, forty-five of her works from the gafakka were made available to Jean Boyd by Wazirin Sokoto, Alhaji Dr Junaidu, a great grandson of Nana Asmau who lived in the same house she lived in. He died in the year 1997. Her room is still in the residence of the Wazirin Sokoto (the house is called Gidan Karaatu) and that is where the regalia of the Waziris are kept. Including the metal ring given to Gidado by Abdullahi bin Foduye and the sword given to him by Muhammadu Bello.

Next to the room so full of history, is the class room in which Asma’u taught generations of pupils. The works made available to Jean Boyd were translated into Hausa from ajami by Alhaji Sidi Sayudi and Alhaji Muhammadu Magaji and later on translated into English.

It is possible that some of her works were lost by various means due to the vagaries of time and circumstance but about twenty-one more works were recovered which brings the total to sixty six. Among those sixty-six works, two were not originally hers but works she translated into Hausa. One of which was written by Shehu “Be Sure of God’s Truth” and the other “Yearning for the Prophet” written by Muhammad (Mamman) Tukur. Although she added notes on the works to broaden the explanations to a lay man’s understanding using Takhmis, an Arabic poetic device which is a technique of adding three lines to an existing couplet. Two have also been confirmed to be forgeries, one to be an elegy and one to be a praise song written for her. Six of those copies are her works that she translated to other languages which brings about a total of 56 of her works translated into English (including her translation of the two poems) by the year 1997, a work initiated by Jean Boyd and Beverly Mack. There are also poems she co-authored with other scholars of that time. She was also discovered to have written 19 elegies. After her death Nana Asma’u was buried near her father in the hubbare.

Two centuries after the start of her work, Nana Asma’u remains an inspiration to educated Muslim women who believe that they can make themselves better members of the society and help others do the same.

“Whatever we achieve is indigenous. The ideas did not come from USA, UK, or Saudi Arabia we have a model her. We may need to learn about technical advances from other cultures but our genesis, our initial upbringing, our development is through Nana Asma’u. We believe in what she did. She remains an ideal person to emulate.” -Prof Sadiya Omar

Written by Fatima Hamza Maishanu

Sources:

- The Collected Works of Nana Asma’u Daughter of Usman Danfodiyo by Jean Boyd and Beverly Mack

- One Woman’s Jihad by Jean Boyd and Beverly Mack

- Ibadan History Series, The Sokoto Caliphate by Murray Last

- The Sokoto Caliphate, History and Legacies, 1804-2004 Volume Two

- The Heroes and Heroines of Hausa Land edited by Ibrahim A. Malumfashi, Aminu I. ‘Yandaki and Ibrahim S.S Abdullahi

- The Significance of The Life and Works of Waziri Usman Gidado bin Laima to The Muslims in Nigeria by Ahmad Bello

- Yan Tarun Nana Asma’u Dan Fodiyo, Tsarinsu da Taskace Waqoqinsu by Prof Sadiya Omar